The Roots of a Strange Fruit

This page is under construction

In the only monograph-legnth history of Denton County (1919), Edmund Franklin Bates wrote of returning Confederates:

"...the majority of the Denton County soldiers who were permitted to return home after the war were either emaciated, worn, weary, diseased or wounded --not conquered, but overpowered -- not whipped, but outnumbered -- still believing in States' rights and preservation of property rights. They made the best class of citizens. They had no negroes to be freed. There was not over one soldier in one hundred from Denton County who owned slaves. Their loss was one of principle, the right to secede from the Union. They, in good faith, yielded to the force of majorities and neeeded no reconstruction."

If Texas had left the union to preserve chattel slavery ten years earlier, Bates would have been correct in his assessment of the proportions of solders and enslaved. In 1850, the people of Denton County enslaved 10 people; however, just four years later the number of people held in bondage was 198.

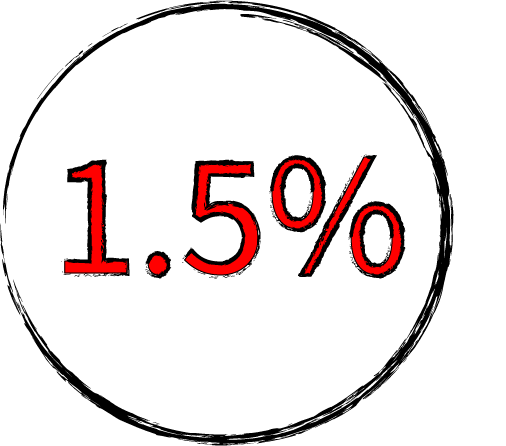

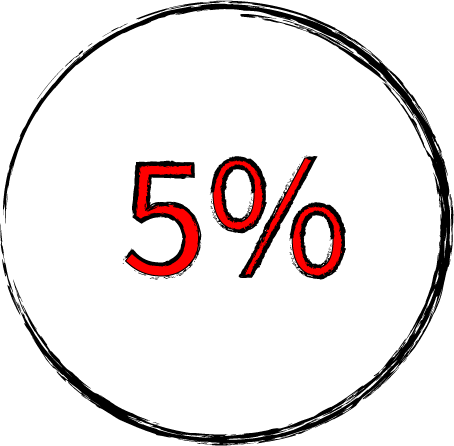

Percentage of the fledgling and frontier Denton County in bondage in 1850 and 1860.

As a percentage of the 585 men who fought in the Civil War from Denton County, the enslaved population was forty-three times greater than Bates's estimate. Another way of viewing this statistic is that 10% of Denton County were either enlisted or conscripted (or both) into Confederate service while 5% of the population of the same county was enslaved. For every two Confederate soldiers there was at least one person in permanent and heritable bondage.

The Ku Klux Klan

What began as an exsoldier fraternal organization in Pulsaki, Tennessee, on December 24, 1865, seeped into the blood-drenched soil of the South and surreptitiously saudered disenfranchised ex-Confederate power-brokers with working class veterans. By the spring of 1867, The Ku Klux Klan emerged in former Confederate states as a full-fledged terrorist organization poised to wage an unrelenting, guerilla-style Civil War against northern allies and interests on Southern soil.

What began as an exsoldier fraternal organization in Pulsaki, Tennessee, on December 24, 1865, seeped into the blood-drenched soil of the South and surreptitiously saudered disenfranchised ex-Confederate power-brokers with working class veterans. By the spring of 1867, The Ku Klux Klan emerged in former Confederate states as a full-fledged terrorist organization poised to wage an unrelenting, guerilla-style Civil War against northern allies and interests on Southern soil.Unable to lash out at the North directly, The Ku Klux Klan attacked Black people, families, and communities. Their costumes allowed the white citizenry to 'know nothing' about acts of racial terrorism, membership in the paramilitary organization, or plans for future attacks. As a result, the Klan operated without impunity for three years. In particular, the Klan organized to prevent the Black vote prior to Texan redemption. One agent for the Freedmen's Bureau in Sulphur Springs so feared the control and violence of the Ku Klux Klan that he went to Dallas to mail his update letter -- not to the assistant commander, but directly to a newspaper so that it would not be intercepted.

"I am aiming to send this letter to Dallas, to have it mailed. It is impossible to have anything of the kind sent from this county by mail. The postmasters are all Ku Klux."

Unfortunately, the fears of Joe Easley were well-founded and he was killed within months of the publication of his letter. In 1868 alone, the fleeing Freedmen's Bureau reported 386 cases of murder or attempted murder against freedmen in the South.

Related Collections

Violence against freedmen in Sulphur Springs

Stuff that happened in Sulphur Springs in 1868.

View the items in Violence against freedmen in Sulphur Springs

Reconstructing North Texas

One unique feature of Denton County during Reconstruction was the political rudders operated by the Denton Monitor. In 1868, Mayor J. A. Carroll convinced the newspaper owner and editor in Greensville to pick up shop and move to Denton. The pair accepted the offer on the spot, moved to a location on the square, and began a long love affair with Denton County. Cheered by its citizens and begged into existence by its political elite, the Denton Monitor was revolutionarily moderate in an ocean of journalistic slant. This is not to say Burnett and Geers avoided controversy -- to the contrary, the Denton Monitor began type-written fisticuffs with papers and politicians across the state and nation in its first printing. While deeply racist and anti-Northern, Geers and Burnett regarded The Ku Klux Klan as a Northern ploy to get the South into trouble and maintain military control. Their rebuke of the Klan was as scathing as their disdain for the carpetbaggers, members of the Loyal League, Black members of the Denton community, and journalists who liked any of the aforementioned.

It isn't that Geers and Burnett opposed racial violence or terrorism; rather, they believed The Ku Klux Klan was a conspiracy by the North. While praising the work of lynchmobs in one column, the pair of newly minted Dentonites mocked Klan-sympathizing publications in the next. Across the state and around the country, the fundamentally different political views of the Denton Monitor were both beloved and derided, at times by the same publication.

At home in Denton County, the Denton Monitor was a source of pride for decades.

Electorial success of the KKK and redemption

Enforcement Acts